Reflections - Mystery in Neon Green Part Two

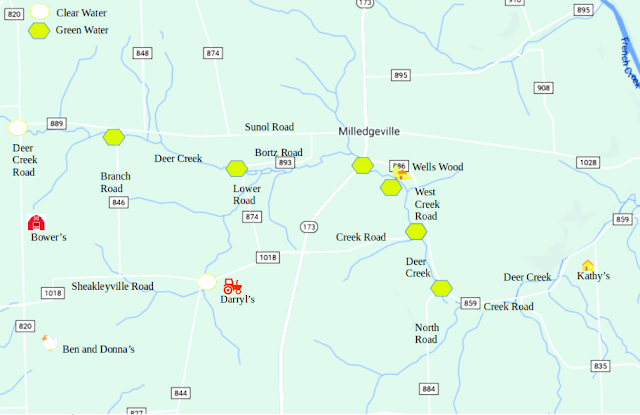

| JW's Version of the Neon Green Mystery Map |

The morning of August 12, Larissa, the Watershed Specialist from Mercer County Conservation District, arrived at Wells Wood first. Wearing masks, we perched on porch chairs with our knees almost touching and held her map between us.

“That’s not right.” I touched the blue road where Wells Wood should be. “We’re on the south side of the road.”

“Oh, that’s the creek. Blue is water. Roads are white. I don’t know why.”

Blue for water made sense. White roads on a white background didn’t. Squinting, I willed my eyes to adjust. “Your green stars correctly mark each green water site.”

She circled her finger around an area between Deer Creek and Branch Roads. “The occurrence must have started somewhere here.”

An engine rumbled on West Creek Road then gravel crunched on the driveway. Dan from DEP had arrived. Larissa hustled off the porch to get her gear.

The two scientists slipped into thigh high boots.

“Which lab are you using?” Larissa asked Dan while tucking protective gloves into her windbreaker pocket. As an aside to me, she said, “The weather doesn’t require a jacket, but mosquitoes think I’m tasty.”

Dan shoved pint bottles into a plastic bag. “Bureau of Laboratories.”

“That’s the lab we use!”

They decided he could take the samples because he’d already called the courier.

I led them across the field and through the woods to the creek.

Wearing protective gloves, Larissa rinsed the bottles in clear creek water then Dan submerged them halfway into the isolated pool. Green water oozed inside.

9-8-20 Dan Taking a Sample of Green Deer Creek

While he screwed on lids and stowed the samples, Larissa studied rocks. “They have a green ring around their bottoms from where the water receded.”

On the way back to their trucks, I quizzed the scientists. “What caused this?”

“Nutrient loading,” Dan said as if that would mean something to me.

“Nutrient loading?” Once I start, a cascade of questions pours from my mouth.

“Lots of nutrients for algae or other organisms,” he said. “Nutrients could come from runoff, septic tanks, or ponds.”

“Why now?”

“You had compounding circumstances—water heating up this time of year, nutrients available, and sunlight. Well,” Larissa cleared her throat, “not a lot of sunlight in the woods, but enough.”

Even though blooms rarely occur in freshwater streams, they agreed an algal bloom caused the green water, not a spill.

Larissa handed me several fliers about Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs). “Like the flier says, ‘When in doubt, stay out.’”

“I’ll let you know when the results come back.” Dan stowed the samples in a portable chest and positioned a bag of ice over them. “Oh, and Spence’s report didn’t go through the computer. I filled one out for you.”

That explained why no one from DEP had called Monday though Spence had filled in an online form about neon green Deer Creek Saturday, August 8.

After two days of their concentrated calls and visits, I figured their follow up would come quickly.

It didn’t.

Five days later Dan called. “It was blue-green algae so I need to take more samples. I’ll be out early Thursday morning. The lab will do the toxicity tests and let us know.”

Thursday Dan crouched by the green pool, which had evaporated to a third the size that it was when Dan first saw it. “This is microcystis which can produce the toxin, microcystin.” He rinsed the bottles and collected samples. “Depending on the toxin level, the public health department will post warning signs.”

“Why does the blue-green algae look like a paint spill—not an explosion of plants?”

“Blue-green algae isn’t really algae. It’s a cyanobacteria, a single celled organism.”

I bit my lip to prevent myself from questioning Dan further.

Expecting speedy lab results, I called Kathy, our neighborhood’s equivalent of social media. “We still haven’t heard if the blue-green algae released any toxins.”

“Geeze,” Kathy’s voice came over the phone line. “They sure are taking their time.”

“Does everyone know? Did you tell the folks with the horses by the hard road?”

“Yeah. Frank and them know. Let me think.” Crickets chirping in our field filled Kathy’s pause. “I could call Charlie. He’s got that little white dog. He walks it up the road then sits on the bench by the crick.”

Spence distributed HABs fliers to neighbors including Ben at the egg farm. The half hour egg trip took an hour that day. Ben discussed the dry weather, his sons starting school, and great blue herons decimating area frogs. Then the conversation turned green. “The people that bought Bower’s drained the pond behind the barn.”

“They did?” Spence straightened to full height.

“You can see it from the road when you drive by. I saw a backhoe out there about two weeks ago.”

Spence drove by the empty pond then came home with the news.

“Nutrient loading!” I emailed the scientists, but they'd already left the office for the weekend.

Tuesday, after a brief morning rain shower, I escorted Spence while he drove his tractor. Flashers blinked, and the car speedometer registered zero miles per hour all the way up Route 173 hill.

Once he parked the tractor at the shop and explained the tire problem to Darryl, our neighbor and tractor mechanic, Spence slid onto the passenger seat beside me. “Do you want to see Bower’s empty pond?”

“Definitely!”

He chuckled, directed me to Deer Creek Road, and coached. “Keep going . . . a little farther . . . at the top of that rise.”

Slowing the car, I glanced at the former cow pasture. Behind the barn, a shallow, depressed oval stretched eighty by thirty feet. No water. No green. Just mud from the earlier shower. Pond water had flowed downhill to a feeder stream which emptied into Deer Creek.

Larissa’s circling finger had included Bower’s old pond.

Dan called that afternoon. “The second test showed the same kind of blue-green algae. There’s no word yet if it is toxic or not. I don’t know what’s taking so long.”

The next morning, August 26, eighteen days after Spence and I had discovered the green water, we joined Larissa and Dan beside the now half gallon-size green puddle.

While Dan bent to rinse the bottle in clear water, I asked, “Did the clear part of Deer Creek have blue-green algae?”

“Yes, the normal amount found in streams.” He returned to the green water. “Not enough to be concerned about.”

Larissa walked over the rocks and pointed. “Here’s a smear of algae that looks like neon green paint.”

I picked up the rock for a better view of the postage stamp-size smear.

“Wash your hands real well when you get back.” Larissa used her calm voice, but her eyes flashed concern. “Don’t touch your face. Use COVID-19 precautions.”

Replacing the rock on the island between the main stream and green pool, I fought the urge to scratch my nose.

|

| Leopard Frog |

A leopard frog poked its head out of the clear water.

We traipsed back to the house.

“I can’t go on private property,” Larissa said to Dan’s back while he stowed the samples in his truck. “When I follow you to Bower’s farm to look for evidence, I have to stay on state game land.”

Dan nodded, and they drove off to investigate Bower’s empty pond.

I waited, not patiently, for a call. In the meanwhile, remnants of hurricanes Marco and Laura saturated Wells Wood and flushed the contents of the tiny green pool downstream.

Dan finally sent an email Wednesday morning, September 2. After studying his message, loaded with science terms and containing two tables and seven spreadsheets, I yelled, “Yikes!” Our little green pool had elevated Microcystin level—yellow warning on the first test and red danger on the second. When he called to follow up that afternoon, I asked about toxins in other parts of the creek. Kathy would want to know.

“They found the normal level of toxins for the creek. The toxins probably came and went.” His scientific voice changed to whimsical. “I wish I could have taken samples when the creek was green.”

After waiting a whole week, I had to satisfy my curiosity. “What did you discover about Bower’s pond?”

“The time, place, and draining of the pond fit with the occurrence. After all the work I put into this, someone else will follow up on the pond. They need to find out what it was used for and what the nutrient might be.”

“When Mr. Bower had cows, they drank from the pond.”

Dan sighed. “Cows poop all over. Runoff would have filled the pond. With the dry weather, the nutrients would have been concentrated.”

I didn’t mention the pheasants, that the Game Commission stocked for hunters, strolled from the game land to Mr. Bower’s barn. They added more poop to the old cow manure.

Dan came for more samples on September 8, exactly one month after the start of the neon green mystery. Chatting about his kayaking at Presque Isle and my apple picking over the holiday weekend, we walked to the creek one last time.

“I’ve never seen the creek so high.” He pulled bottles from his plastic bag.

The creek wasn’t high. It only rose a quarter of the way up the bank and left a rock island in the middle.

Dan dipped a bottle. “ Hmmm. These minnows are feisty fellas.” He emptied it and dipped it again. “They’re challenging me.”

9-8-20 Dan Taking the Final Sample

Minnows darted in the pool because rains had flushed the toxins away. They would be diluted to insignificant through creeks then rivers on their way to the Gulf of Mexico.

I received a final email from Dan a week later. It said what the minnows had already told me. The former green pool didn’t contain any blue green algae.

Spence took copies of DEP’s follow-up report to the township meeting.

I called Kathy.

The neon green mystery was over for now. With warmer, drier summers and abandoned dairy farms in the neighborhood, Dan said, “I’m glad you watch the creek on your walks.”

Thresholds for Response Levels